To listen to this article, please log in.

Haiti : The revolution of the slaves

In August 1791, first a slave rebellion broke out in the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue, then a revolution broke out. In 1804 Haiti emerged, the first and only state in world history founded by former slaves. by Hakan Baykal Loading … © Costa/Leemage/picture alliance (Excerpt)

Loading … © Costa/Leemage/picture alliance (Excerpt)

“I was one of your soldiers and the first servant of the republic, but now I am miserable, ruined, dishonored, a victim of my services!” So wrote one general to another in 1802; a revolutionary, general and lawgiver to one such; a prisoner abducted from his homeland for a man who was still facing this fate. Toussaint Louverture wrote it to Napoleon Bonaparte. The two had never met each other personally, but had occasionally spoken to each other across the ocean for a number of years, assuring each other of their mutual respect and sympathy. But now it was over with the courtesies.

Napoleon (1769–1821) & nbsp; – as the first consul of the French Republic since 1799 at the provisional height of his power & nbsp; – had enough of the rebel from overseas. Louverture's last, desperate letter went unanswered. He wrote it in the fortress of Fort de Joux in the French Jura, where Napoleon had him imprisoned under the toughest conditions.

Toussaint Louverture was born in 1743 as a child of slaves on the plantation of the Count of Bréda near Cap-Français, the capital of the French colony of Saint-Domingue. Little is known about the first five decades of his life. Apparently the boy, whose father probably came from what is now Benin, received a relatively good education. Since Toussaint Bréda, as he was originally called after his owner, had a weak constitution, his master allowed him to learn to read and write. Later the aristocrat employed his slave as a coachman and estate manager – both privileged positions within the slave hierarchy. In 1776 the count released him into freedom. Toussaint acquired his own small coffee plantation, for the management of which he is said to have used up to a dozen slaves at times.

Loading … © AKG Images/Manuel Cohen (excerpt) Toussaint Louverture (1743-1803) | When it turned out in the course of the revolution that the French were not prepared to make any concessions to the slaves, Louverture took the lead in the uprising. Portrait of Denis Alexandre Volozan, around 1800.

Loading … © AKG Images/Manuel Cohen (excerpt) Toussaint Louverture (1743-1803) | When it turned out in the course of the revolution that the French were not prepared to make any concessions to the slaves, Louverture took the lead in the uprising. Portrait of Denis Alexandre Volozan, around 1800.

Toussaint was a relatively educated man. In addition to his mother tongue, the West African Fon, he mastered both Creole and French, and read ancient classics such as Caesar's writings and works of the Enlightenment. Gradually the freedman increased his property, in 1782 married the former slave Suzanne Simone, who gave him two sons. Toussaint Bréda became a wealthy, respected man. So a life that began in slavery could have continued until its happy end – and no one would have known about it. If 15 & nbsp; years after Toussaint's release a violent storm had not struck his home island, the effects of which could also be felt in Europe: the slave revolt of 1791. It only ended in 1804 after a long, bloody struggle with the establishment of the independent state of Haiti.

Jürgen Osterhammel, professor emeritus for modern and contemporary history at the University of Konstanz, explains a change that could succeed, “because here and only here an outside force, the French Revolution, divided the white gentlemen's caste; because here and only here there was a wealthy intermediate class of free colored people (“gens de couleur”) who used the confusion of the whites for their own elevation; and because here and only here an international conflict was waged over a sugar island, in which the powers involved – France, Spain and Great Britain & nbsp; – armed slave mercenaries «.

How the first colony of Europe came about

To understand how this unique constellation came about, it helps to look back. During his first voyage across the Atlantic in December 1492, Christopher Columbus discovered the island, which is now shared by the states of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. He gave the island, which was called Ayti by its natives, the name La Isla Española (Hispaniola) and had a small fort built there from the planks of the damaged “Santa Maria”, the first Spanish colony in the New World & nbsp; – and with it the first ever European.

Almost immediately, the Spaniards planted the first sugar plantations on the island, on which they forced members of the local Arawak people to do slave labor. Within a few decades, the people, who numbered an estimated 250 & nbsp; 000 to 400 & nbsp; 000 & nbsp; souls when the Europeans arrived, were as good as exterminated & nbsp; – destroyed by slavery, slaughtered in battles and carried away by diseases that were introduced. As early as 1503, the Spanish colonists were therefore also using slaves from Africa in the ore mines and on the island's plantations. In the course of the following decades, however, the development of the colony slowed down.

The Spaniards were primarily looking for precious metals. However, as Hispaniola's sparse gold resources were running low, many lost interest in the colony. Soon the island served only as a bridgehead on the way to the more productive possessions on the American mainland. In the 17th & nbsp; century, French privateers settled in the west of the island and laid the foundation for the conquest of France. In 1697, Spain officially ceded the western part of the island to the country.

The slaves produced luxury goods for Europe

The new settlers accelerated the plantation economy, and so in the 18th & nbsp; century Saint-Domingue, as western Hispaniola was now called, became one of the most profitable colonies of that time – thanks to the mass deportation and enslavement of Africans, mainly from the area of the today's states of Gambia and Senegal. In this way, a slave society emerged on the Caribbean island within a few years. Slavery was the means of all production.

The prerequisite and motor of this development was the growing desire of the Western European population for luxury goods from overseas. Sugar, coffee, cocoa & nbsp; – as the demand for these goods increased in the old world, so did the demand for cheap labor on the plantations of the new. Transatlantic human trade increased rapidly. “The 18th century, known to be the century of the Enlightenment, was also the most terrible century of deportations,” emphasizes Michael Zeuske from the Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies at the University of Bonn. Altogether, from around 1500 to the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade around 1850, around twelve million Africans were brought into the North and South American colonies & nbsp; – around half of them in the age of Voltaire alone.

Sainte-Domingue constantly demanded Slaves

With thousands of highly profitable plantations on which African slaves toiled, Saint-Domingue was considered one of the most profitable colonies of that time. But the demand for new workers was high, which had an impact on the population structure. At the end of the 1780s, in addition to a little over 30 & nbsp; 000 & nbsp; white Europeans, there were roughly as many free and in some cases equally wealthy “gens de couleur” in the colony. They were mostly the descendants of the French and slaves or freedmen like Toussaint Bréda. Together they had around half a million black slaves. »Almost 90 percent of the people living in the colony were the property of another person«, writes the historian Philipp Hanke in his book »Revolution in Haiti«.

Loading … © Alamy/Niday Picture Library (excerpt) Burning Capital | View of Cap-Français on June 21, 1793. In the midst of the revolution, the capital is burning on the north coast of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. Colored print by Jean-Baptiste Chapuy, c. 1794.

Loading … © Alamy/Niday Picture Library (excerpt) Burning Capital | View of Cap-Français on June 21, 1793. In the midst of the revolution, the capital is burning on the north coast of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. Colored print by Jean-Baptiste Chapuy, c. 1794.

The development of social structures in Saint-Domingue took a separate path within the slave societies of the Caribbean. “In contrast to other large plantation economies of the time, society does not present itself as a simple two-class system,” explains Hanke. In the British colony of Jamaica, for example, the situation was clear: white Europeans had all power and possessions, blacks and Creoles had to serve as slaves. In Saint-Domingue, on the other hand, a society emerged “that consisted of four classes, some of which were economic and some were defined by skin color,” explains Osterhammel.

The top layer was made up of wealthy European plantation owners and members of the island bureaucracy, the so-called “grands blancs,” the great whites. Formally equated with them as subjects of the French king, but in fact excluded from public life and all political decisions, were the free “gens de couleur”, many of whom had also made considerable fortunes as planters. Their prosperity aroused envy among the so-called little whites (“petits blancs”). They were mostly overseers on the plantations or traders and artisans in the cities, originally coming from a humble background in France. The bottom layer was made up of the mass of slaves, around two thirds of whom were born in Africa.

A brutal set of rules for dealing with slaves

The so-called »Code & nbsp; Noir« provided the legal framework for slavery. The King Ludwig XIV. A decree issued in 1685 stipulated who could keep slaves and how they should be traded and treated. The slave owners were expressly allowed to chain and beat their human property, but they were forbidden from torturing their slaves or killing them for no reason. But if a slave raised his hand against his master or his family, he was threatened with execution. The set of rules did not protect the enslaved Africans from arbitrariness.

The “Code Noir” was valid until 1848, after which it was forgotten. The French philosopher Louis Sala-Molins rediscovered the decree at the end of the 1980s and complained that hardly any of the French enlighteners had commented on it. An exception was Guillaume Thomas François Raynal (1713–1796), who in his “History of the Two Indies” (“Histoire des deux Indes”) castigated the inhumanity of slavery and prophesied that this tyranny would one day lead to a “black Spartacus” Will bring forth enslaved against their white masters. The encyclopedic work was banned and publicly burned, its author reviled and driven out of the country for a few years. But he was proven right.

The values of the French Revolution stopped at slavery

The politicization of large parts of the French population during the 1780s also spread to the kingdom's colonies. As early as 1788, the “Société des Amis des Noirs” (Society of Friends of Blacks) was founded in Paris, which campaigned rather marginally for the abolition of slavery, but especially for the actual equality of the free “gens de couleur”. With the beginning of the French Revolution the following year, especially with the declaration of human and civil rights on August 26, 1789, the cause received a considerable boost. Finally, the first article of the Declaration stated unequivocally: “People are born free and equal in rights and remain so.”

The abolition of slavery in the colonies was rejected by the Paris National Assembly on the grounds that it would damage the French economy. Neither the free nor the enslaved blacks wanted to submit. Vincent Ogé, one of those planters who had witnessed the indifference of the National Assembly in Paris, decided to act. In July 1790 he led the first armed uprising of Creole plantation owners at Saint-Domingue. The revolt, in which, according to his will, no slaves took part, failed miserably. Ogé was executed together with 20 fellow campaigners, their bodies put on display.

But the storm could no longer be tamed. According to legend, the slaves in the northern plain of Saint-Domingues rose spontaneously after a voodoo ceremony. Historians assume, however, that “privileged” slaves held several secret meetings in the weeks leading up to the revolt to organize and lead the uprising. In any case, on the night of August 23, 1791, the slaves rebelled on a plantation in the north, in the richest part of Saint-Domingues, where the capital Cap-Français was located.

Thousands and thousands of slaves freed themselves, soon a civil war raged

The rebels set houses and fields on fire, killed their masters and their families and conquered large parts of the northern plain within a few days. Their number rose rapidly: it started with 1,000 to 2,000 insurgents, and less than three months later the colonialists were faced with a force of 80,000 men. Around half of the slaves on the plantations in the north rose under the Creole battle cry “Tou moun se moun” (All people are people) & nbsp; – and there was no stopping them. By the end of the year, thousands upon thousands of slaves had freed themselves. A civil war raged throughout the colony with changing fronts and loyalties.

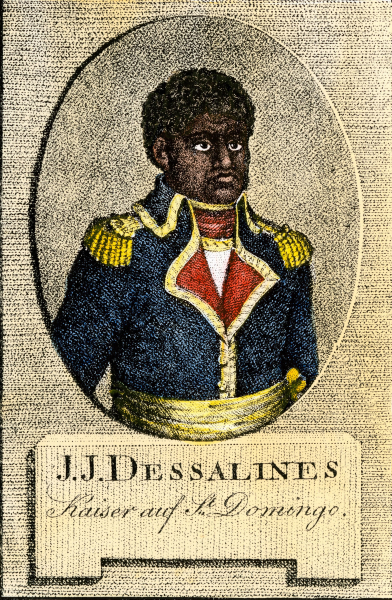

loading … © Alamy/North Wind Picture Archives (detail) Jean-Jacques Dessalines (1758–1806) | After Toussaint Louverture was abducted to France, his companion Dessalines continued the revolution. In November 1803 the former slaves finally triumphed against the French invaders.

loading … © Alamy/North Wind Picture Archives (detail) Jean-Jacques Dessalines (1758–1806) | After Toussaint Louverture was abducted to France, his companion Dessalines continued the revolution. In November 1803 the former slaves finally triumphed against the French invaders.

The “grands blancs” were predominantly aristocrats and had therefore already rejected the survey in their home country. The “little whites” were more likely to be enthusiastic about the ideals of the French Revolution, but often did not want to join forces with the blacks. The leaders of the uprising, on the other hand, had given the slaves hopes that the “white slaves” had chased away their masters in Europe too. Now they wanted to do the same. The free and rich “gens de couleur” were, however, split: On the one hand, they hoped to finally achieve emancipation; on the other hand, they feared that the revolution would lose all property and wealth. In addition, the colonial powers Great Britain and Spain sensed their chance to make a profit from the unrest, and mixed vigorously with & nbsp; – either by armed insurgents or intervening in the fighting themselves.

Toussaint Louverture sidestepped the revolutionaries

It was in this situation that Toussaint Bréda entered the story stage. At first he did not take part in the uprising. He is even said to have protected his former master and his family from the anger of the slaves and saved their lives. “Only when it became clear that the European colonists were not prepared to compromise with the rebellious slaves did he join the rebels,” explains Hanke. Since 1793 at the latest, Toussaint Bréda has shown himself to be one of the most important military leaders of the revolutionaries under the self-chosen name »Louverture«.

At first he fought in Spanish service against the French colonial rulers. But after the National Assembly in Paris in August 1793 had abolished slavery in all French territories and declared all male liberated citizens to be citizens with equal rights, he switched fronts. At that time, the French revolutionary armies in Europe were against a coalition of European powers led by Austria, Prussia and Great Britain. In September 1793, the first 600 British soldiers landed in Saint-Domingue. Over the next five years they should be followed by more than 20 & nbsp; 000, around half of whom succumbed to yellow fever.

The constitution of a new state comes into force

Louverture, who apparently had some strategic skill, managed to unite the insurgents under his leadership and gradually push back the Spanish and British troops and finally defeat them in 1798. Just this year, the board of directors now ruling in Paris decided that blacks born in Africa or the American possessions were to be regarded as migrants in France and that their further status had to be decided individually. However, the slaves who had freed themselves lost their citizenship with equal rights. When it became apparent in 1799 that Napoleon Bonaparte was considering reintroducing slavery, Louverture's loyalty to the French Republic also began to falter.

On February 4th, 1801, Toussaint Louverture signed the Constitution of Saint-Domingue. “Under the conditions of colonialism, an order based on freedom and equality should be established,” writes Hanke. The constitution was the first ever to explicitly rule out the mere possibility that one person could be the property of another. That was unique. Although in the previous years Maximilien de Robespierre (1758–1794), among others, had urged that a ban on slavery be enshrined in the French constitution, this had not happened. Such a ban was not to be expected from the only other modern republic in the western hemisphere, the United States, & nbsp; – many of the founding fathers were slaveholders themselves, above all the then incumbent President Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826).

The constitution for Saint-Domingue did not contain any separation from France, but Napoleon understood it as such. In a letter to Louverture, he wrote that it contained something “which ran counter to the pride and sovereignty of the French people.” In February 1802, a French force of more than 20,000 men landed in Saint-Domingue under the leadership of General Charles Victoire Emmanuel Leclerc (1772-1802), Napoleon's brother-in-law. Their mission was to arrest Toussaint Louverture, pacify any uprising and enforce the reintroduction of slavery.

France could no longer get the colony under control

Leclerc did the first part of his job immediately: Louverture was captured in early June 1802 and deported to France. Only ten months later, on April 7, 1803, he succumbed to the consequences of the conditions of his detention. The pacification of the colony, however, was far more difficult. “It is necessary to destroy all black people in the mountains, men and women, only children under twelve should be spared,” wrote Leclerc to his brother-in-law. Otherwise the colony could not be brought under control.

The general was right, but was no more to see the day the colony was lost to France than was Louverture. Like many of his soldiers, he died of yellow fever. The blacks of Saint-Domingue, who had liberated themselves, fought under the leadership of Jean-Jacques Dessalines (1758-1806), the companion and successor of Louverture, against the French invaders and defeated them in an all-important battle in November 1803 On January 1st, 1804, the victorious general proclaimed the independence of his homeland, which was now called Haiti based on its original name.

Both the European colonial powers and the USA failed the young state for decades the acceptance. In 1825 France was ready to recognize Haiti as an independent state – under extreme conditions. “The agreement with France is one of the rare examples in history in which a militarily victorious country was forced to pay reparations for its independence,” says Hanke. For the recognition of its independence by the former mother country, Haiti had to agree to pay the enormous sum of 150 & nbsp; million gold francs & nbsp; as compensation not only for the loss of land, but also explicitly, under threat of a new invasion and the reintroduction of slavery for the lost human capital, the slaves. The effects of these reparations, which Haiti had to pay until 1947, were devastating for the country that is still one of the poorest in the world today.